By William Shaw

The 1990s music scene produced two moments of great darkness. If the 1994 death of Kurt Cobain somehow symbolised young white alienation, the murder of Tupac Shakur two years later continues to resonate, not just because it was another deep and painful scar for the African American community, but because no one has ever been prosecuted for it. And it looked, for two decades, like no one ever would be.

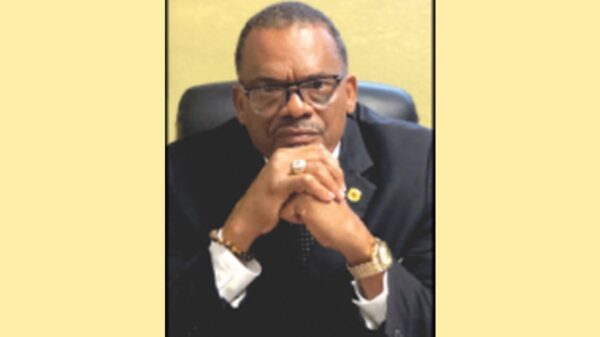

It was something of surprise, then, when armoured cars rolled into a quiet suburban street in Henderson, Nevada last month in the sweltering 40C of a July evening and armed officers ordered out the occupants. “Come out with your hands empty,” shouted police. A middle-aged man and a woman exited, walking backwards towards the waiting officers. They were executing a search as part of an investigation into the killing of Shakur. The house belongs to Paula Clemons, wife of 60-year-old Duane Davis, better known as gang leader and former high-profile Los Angeles drug dealer Keefe D.

To anyone who loves hip-hop, Shakur is a giant. He sold more than 75m records and starred in six movies. In the 90s, African American culture was at an extraordinary creative peak, but it was also grappling with extremes of toxic masculinity. Shakur’s music is full of anger at the poverty inflicted on his generation and at the extraordinary violence perpetrated both by and against it. It’s not surprising, then, that when he was shot dead, everyone wanted to know why. After 27 years, Las Vegas police, who fumbled the initial investigation, appear to be attempting to uncover new evidence. The idea that we may be about to finally discover the answer is tantalising.

When all this happened, I was living in Los Angeles, writing a book about hip-hop and about the young men of South Central LA, many of whom dreamed of a stardom that could lift them out of their toxic lives. The first time I met Shakur was at the pink palm-treed fantasy that is the Beverly Hills Hotel. Shakur had recently signed to Death Row Records, owned by Marion “Suge” Knight. Already a major star, Shakur had been convicted and imprisoned in 1995 on a charge of sexual abuse of a fan. With major labels wary of his reputation, Knight took it as an opportunity. He posted $1.4m bail to have Shakur released from Clinton Correctional Facility, New York, pending appeal. Shakur felt he owed Knight his freedom. That would turn out to be important.

Shakur talked about the shooting in 1994. ‘I know I’m not going to live for ever. I know I’m going to die in violence’

Shakur was ecstatic to be back. We sat in a restaurant at a table next to Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson. “After 11 months inside, this must be something of a relief,” I said.

“Exactly,” said Shakur, happily ordering a double helping of soft-shell crab. “When I sat there [in prison], this is what I thought about.”

Shakur was pure charisma. He could do urbane and cultured, quoting Robert Frost as we ate. But after the meal we got into his open-top Jaguar. At a junction, a nearby car backfired and Shakur tensed. Later he told me he did that all the time. Eighteen months earlier in New York, Shakur had been shot in a botched robbery outside a recording studio. He was suffering from PTSD.

That afternoon we drove on to Death Row’s Can-Am Studios in the suburb of Tarzana so Shakur could play me tracks for his forthcoming LP All Eyez on Me – a double album that would sell more than half a million copies in its first week. The industrial unit had been turned into a heavily guarded fortress. Once inside, Shakur started smoking weed. Among musicians and friends – including a young rapper called Yaki Kadafi – his demeanour was relaxed, but as he talked, a darker side emerged. He talked about that shooting in 1994.

“Right now, I know I’m not going to live for ever. I know I’m going to die in violence.”

Does that make you afraid?

“No. I’m not afraid of the niggas coming for me, or what they might do. Because it’s going to happen. All good, niggas. All the niggas who change the world die in violence. They don’t get to die in regular ways. Motherfuckers come to take their lives.”

By then he was pretty stoned. Honestly, I didn’t think for a minute that what he was saying had much to do with reality.

Shakur’s mother, Afeni Shakur, was a Black Panther and political activist. He had grown up believing his father was a drug dealer known as Legs who died of a heart attack when Tupac was 15. (Later, when Shakur was in hospital after the New York shooting, a former Black Panther named Billy Garland appeared at his bedside to announce that he was his real father. “I had to be there,” Garland told me. “I just wanted to let him know that I cared.”) Shakur had gone through all his later teenage years thinking he was fatherless, and it was a topic he returned to in his lyrics. I remember talking to him about it on another day at his apartment on Wilshire Boulevard.

When did you first start looking for a father figure?

“When I started seeing other people, and how they handled it. I was like: ‘Damn! Why do I have to drink? Why do I grind my teeth when I sleep? Why is it so mandatory that I get respect?’ If you call me bitch, we’re going to fight. That’s what I have constantly to work with. It wasn’t reinforced that I was a man. So I can’t let nobody shake it because I might die that second they called me bitch, and that can’t be the last thing they called me.”

It was Shakur’s ability to alchemise anger and hurt into performance that made him an extraordinary artist.

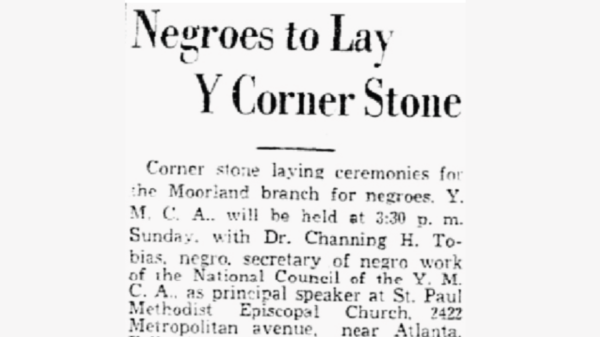

To get to the root of this story, you have to understand something of LA gang culture. South Central was a ghetto created by racist Jim Crow laws. When southern labour flooded northwards in the first half of the 20th century, it found itself confined to neighbourhoods around Central Avenue, south of the city centre. Communities struggled for decent housing, schooling and basic amenities. This catastrophe was built-in. Where you lived became an area with strict boundaries, surrounded by hostile white communities.

Following the Reagan-era welfare cuts, drugs flooded Los Angeles. With drugs came a tsunami of violence

A generation of young political leaders was effectively eliminated in the 60s and 70s by the FBI who targeted the emerging Black Panther movement. Some were imprisoned, others covertly assassinated; the movement was infiltrated and deliberate misinformation was used to spread disunity. It worked. In the absence of leadership, local gangs proliferated. South Central became Balkanised into defensive territories.

In late-60s LA, a super-gang known as the Crips emerged, attempting to emulate the Panthers by forging an alliance of these micro territories. The Crips grew rapidly until they met with resistance from the remaining independent gangs – one of which was a set called the Pirus who were based in Compton. Those who opposed Crips became known as Bloods. Each local outfit forced you to pick sides. Either you were a Blood, signified by the colour red, or a Crip, blue. Young men not only had to negotiate the territoriality of local gangs, they now had to deal with this secondary layer of complexity, stretching across the entire city.

Following the Reagan-era welfare cuts, drugs flooded the city. With drugs came a tsunami of violence, peaking in 1992, a year when there were 803 gang-related deaths in Los Angeles County alone.

Compton created Bloods and Crips; a rap group called NWA made them world famous. Founder Eric “Eazy-E” Wright was from an outfit known as the Kelly Park Compton Crips. Their breakout was 1988’s Straight Outta Compton. From the start it was about where you were from.

But it was Suge Knight’s Death Row Records that got the whole world talking about Bloods and Crips. If Eazy was loosely affiliated with Compton Crips, Knight made it absolutely clear he was with the other side. His affiliation was with the Mob Pirus, a subset of the original Pirus. Knight’s payroll included several of the gang’s members. Not all his artists were happy. One early signing, Dr Dre, abandoned the label, but by then Death Row had acquired its greatest artist of all: Tupac Shakur.

Fresh from incarceration, Shakur was indebted to Knight, and so a man with a troubled sense of masculinity was now surrounded by hardcore Mob Piru members. The levels of violence and murder in this period, the gangland omertà and the astonishingly low conviction rates, created intense paranoia. People died but it was rare to discover who had killed them or why.

There was another wrinkle to the 1994 New York shooting. Shakur’s own version of the paranoia was that a former friend, New York-based rapper the Notorious BIG, and his label head, Sean “Puffy” Combs, had been behind the shooting. Both vehemently denied involvement but rivalry between the east and the west grew fast. Knight stoked it, taunting Combs, threatening in public to poach his artists.

Around three weeks before the murder of Shakur, there was an insignificant scuffle at a shopping mall in Lakewood, north of Long Beach, between members of the Mob Piru and the South Side Compton Crips.

The South Side Crips had emerged as a major force in Compton. Among their leadership was Duane “Keefe D” Davis, the man whose Nevada home was raided last month. In the 90s, Keefe D had established a very profitable network selling drugs imported by the Cali drug cartel to cities across America. “At my height, I was moving 300 kilos a month,” Keefe D has boasted. The South Side had power. And they were outspoken enemies of the neighbouring Mob Pirus. The Pirus had taken to wearing gold chains with Knight’s Death Row logo hanging on them.

In the Lakewood mall face-off, at least one of the Pirus had his chain snatched – one belonging to one of Knight’s young hangers-on, Travon “Tray” Lane. In hip-hop, snatching a chain was a low insult – a kind of symbolic emasculation. Among the untrue rumours circulating was one claiming that, incensed by Knight’s taunts, Puffy Combs had promised $10,000 for every Death Row chain snatched. Among those at Lakewood mall that day was a young man called Orlando “Baby Lane” Anderson, the drug dealer Keefe D’s nephew.

Iwas in London when I heard the news that Shakur had been shot, then the news he had died six days later. In an obituary for Details, the New York magazine I worked for, I struggled to fit the many contrary sides of the man into a few hundred words.

On the night of 7 September 1996, Shakur had been in Las Vegas, at the MGM Grand Hotel watching a Mike Tyson fight. Shakur was on top of the world. All Eyez on Me was on the way to going multi-platinum. In the hotel lobby, one of Shakur’s entourage, Travon “Tray” Lane, still smarting from the chain snatch, spotted a young man with a small moustache. Tray pointed out Orlando Anderson to Shakur as a South Side Crip.

Friends of Anderson have told me he was a massive Tupac fan and had probably been waiting to get a glimpse of the rapper; one relation told me he owned every record Tupac had ever made. Shakur marched straight up to Anderson, confronting him. “You from the south?” Manhood envisioned as territory. Shakur’s fist smashed into the side of Anderson’s head and when Anderson fell, Knight joined in, kicking him. It was over quickly.

Anderson’s life was over. In the public imagination, he was the man who had killed the greatest rapper of his generation

Less than three hours later, Shakur was on his way with Knight to Knight’s Club 662 in Las Vegas when a vehicle pulled up alongside theirs on East Flamingo Road. Shakur was an easy target, leaning out of the window to flirt with women in the next car. Eight shots were fired from a Glock .40. Four hit Shakur.

Immediately after the shooting, Yaki Kadafi, who had been in the car directly behind Shakur, told police the assailants were driving a white Cadillac. He believed he could identify the killer. Las Vegas police failed to follow up the lead. Kadafi, who might have been able to identify Shakur’s killer, was shot in an unrelated incident in New York two months later.

It took very little time for Orlando Anderson to be talked about as the killer of Shakur. One source was Compton police themselves. Remarkably, several Compton officers turned out to have been moonlighting as security for Knight, working alongside Mob Pirus. Anderson was arrested, interviewed and released without charge. If there was any evidence, the botched police investigations had not uncovered it.

From that point on, though, Anderson’s life was pretty much over. In the public imagination, he was the man who had killed the greatest rapper of his generation. “He is tall and rangy with an ice cold stare… the quintessential menace to society,” was how one journalist described him.

Back in LA, in 1998, I remember hearing on the tinny radio of my Subaru that Anderson had been shot and killed in a gunfight at a Compton car wash on Alondra Boulevard. It was unrelated to Shakur’s killing. Anderson and a friend, Michael Dorrough, had been in a gunfight with two members of a local gang, the Corner Poccet Crips, over money owed. Police claimed Anderson had started the shooting and been fatally injured. Both Corner Poccet Crips had died of their injuries.

The book I was writing, Westsiders, was about the young African American men of South Central who were the rappers who didn’t make it – the ones who didn’t get to go to the Beverly Hills Hilton. When somebody told me that Anderson had been trying to get into the music business, I became interested in this shadowy figure who was only famous for supposedly killing Shakur.

I drove around Compton, down South Burris Road, looking for the house that Anderson grew up in. It was a nice looking, ordinary suburban house, painted blue. Wind chimes hung outside the front door. There were bars on most of windows in the neighbourhood. The concrete fence posts on South Burris were scrawled with “SS”: South Side.

At the very least, Keefe D had publicly admitted to arming Shakur’s killer, organising the hunt and destroying evidence

I tried visiting Dorrough, the only survivor from the car wash gunfight, in Twin Towers Correctional Facility, where he was being held pending trial. I sat separated by glass but he refused to talk to anyone apart from his mother and his attorney.

I spoke to school friends, relatives. Cold-blooded killer? No way, they all insisted. “He wasn’t that type of person at all,” a former classmate of Anderson’s at Dominguez high school in Compton told me. “He was a real friendly person, real cool.” He didn’t smoke cigarettes and didn’t even drink much. He graduated from high school, they said. Gang bangers don’t graduate.

Anderson’s brother, Pooh, agreed to meet. A quietly spoken, neatly dressed young man, he had won a scholarship to a private high school and gone on to graduate from the University of California at Berkeley after majoring in film. Pooh insisted we got it all wrong. Orlando was an ordinary young man.

So why was he carrying a gun the day he was killed at the car wash? Pooh looked stricken. Because of his reputation as a killer, he told me. People were terrified of him. And he was equally scared of them. A lot of people in South Central Los Angeles carried guns for the same reason.

One day, in July 1999, I called Pooh to tell him that the prosecution in the Michael Dorrough trial had presented forensic evidence to show that it was almost certainly Anderson who had fired the first shot at the car wash gunfight. “It’s impossible,” Pooh said, shocked. He refused to believe the evidence was accurate.

Keefe D’s drug business fell apart. After Shakur’s killing, his Colombian handlers decided he was too notorious to be useful. He slid into obscurity until 2018, when he did something extraordinary: he started to talk. In a Netflix documentary, Unsolved, Keefe D confirmed there were four people in the white Cadillac. The driver had been a man named Terrence Brown. Behind him and Keefe D sat a man named DeAndre Smith and next to him, Orlando Anderson.

Keefe D admitted procuring the Glock .40 pistol and gathering up three vehicles full of men to confront Knight. “Suge and his boys committed the ultimate disrespect when they kicked and beat down my nephew Baby Lane!” he announced. They had waited at Club 662, but when Knight didn’t materialise they set off looking for him. Keefe D didn’t name the killer but he claimed that the fatal shots came from the back seat. That means it would have been either DeAndre Smith or Orlando Anderson. Afterwards, Keefe D drove the Cadillac back to Compton where it was cleaned and repainted.

In some ways, it’s a surprise that it took five more years for Las Vegas police to arrive at Paula Clemons’s house. At the very least, Keefe D had publicly admitted to arming Shakur’s killer, organising the hunt and then destroying evidence.

How much closer does Keefe D’s account get us to the truth? I’m not sure. Maybe part of the reason he spoke was that there’s no longer anyone else to contradict his version of events. DeAndre Smith was a street thug who died of natural causes in 2004. The only other person in the car, Terrence Brown, was found shot dead from multiple gun wounds at a run-down legal high shop in Compton in September 2015. Keefe D is the only witness left. But I don’t think we’ll ever know. It could have been any one of the four men.

To have grown up in South Central in the 90s was to grow up in a firestorm of creativity, passion, desperation and incendiary masculinities. The place is changed now. They have rebranded it as South LA; the African American population has pretty much moved out. I always wanted to believe Anderson’s friends’ version: that a young man, even one who grew up in a family like his, despite all the assumptions, all the environmental pressures, didn’t automatically have to become a murderer and drug dealer. But only Keefe D really knows.

- William Shaw’s most recent novel (writing as GW Shaw) is The Conspirators, published by riverrun

You must be logged in to post a comment Login