By Wayne Dawkins

NABJ Black News & Views

https://blacknewsandviews.com/

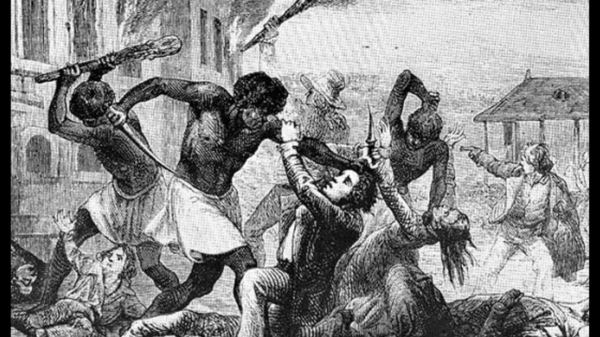

HAVANA, Cuba – Three years after the end of the U.S. Civil War and the Constitutional amendments that freed Black people, made them citizens, and gave the men voting rights, these new citizens advocated for an end to slavery in Cuba.

In 1868, a petition was offered to then-President-elect Ulysses Grant, but the 18th commander in chief did not accept it. Slavery continued at America’s Caribbean island neighbor for 18 more years until 1886.

Now, almost 150 years later, Black writers and scholars from both countries are fresh off of a gathering in Havana to explore the banning of books and where both countries stand in terms of racism.

“Book banning of African Americans is colonialism and reductivism, persistent racism and subjugation,” Marta Bonet, president of the Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba, said at the five-day symposium.

“We are here with great purpose,” said DeWayne Wickham, leader of the 25-member U.S. delegation. “We are under siege in the United States,” added Wickham, an emeritus dean at HBCU Morgan State University, Baltimore.

“We’re here because we have a friend, and a connection that is 150-years-old.”

“Banning Black Books, Silencing Black Voices: America’s Apartheid,” took place at the Casa de las Americas, a cultural center in Havana, and the National Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba.

“Book banning is for the whole world to know,” said Abel Prieto, president of Casa de las Americas. “Cubans learned very early to differentiate between the U.S. government and the American people. Danny Glover, Alice Walker came here. [W.E.B.] DuBois visited Cuba in the 1940s.”

Prieto raised a copy of DuBois’ “The Souls of Black Folks.”

“The analysis we are doing here has a lot to do with Cuba. To visit Cuba is to be banned,” said Kenia Serrano, Ph.D., a University of Havana dean, the previous day. “In 1961, Fidel [Castro] was banned from the United Nations as a head of state, but he was embraced in Harlem. He met with Malcolm X for less than one hour.”

She raised a copy of the book “Fidel & Malcolm X: Memories of a Meeting.”

The Havana hosts reminded or assured the U.S. visitors that Cuba is a hybrid nation of people who acknowledge they are of African and European ethnicity. Yes, racism exists but it is social, unlike written into laws as it was done in the United States.

Such differences explain the parallel paths of Harlem Renaissance writers vs. Afro Cuban writers during 1920 to 1940.

Havana writers found a voice for Africans in Cuba and made it difficult to assert Cuban national identity without embracing both European and African cultures, wrote Ricardo Rene Laremont and Lis Yun three decades ago.

In contrast, Harlem writers, constructed a Black American identity within American European culture so that Black culture would become comparable to white American culture.

Several Black authors whose books have been banned spoke during the gathering. Nikole Hannah-Jones, author of “The 1619 Project” which reframed slavery’s place in America’s history and society, was among them. She recounted her early years in America’s Great Plans.

“My community in Iowa was 15 percent Black, large enough to be segregated and redlined. My father, a World War II veteran, flew a large American flag in our yard. He sent a message: you will not take away my legacy, my birthright.

“[So] Ironically, “The 1619 Project” was the most patriotic thing I’ve done,” Hannah-Jones said of her widely-read work, which also has been widely banned.

The Pulitzer Prize and Polk Award winner was offered a tenured faculty position at the University of North Carolina, her graduate school, but the offer was withdrawn because of objections from a trustee and donor. Hannah-Jones migrated to Howard University and took multimillion-dollar foundation support with her.

“Narrative drives policy,” said Hannah-Jones, “not data or peer-reviewed research. It’s not about fixing broken Black people, but redistributing wealth stolen from Black people.

“Because of George Floyd’s killing before our eyes, white people joined Blacks in the streets. Many of them read ‘The 1619 Project’ in The New York Times, the pinnacle of American journalism. That caused the backlash.”

Indeed. Florida lawmakers guided by Gov. Ron DeSantis passed the “Stop Woke Act,” banning Black history and literature in college-preparatory advanced placement high school classes and in public university curricula..

“Sorry y’all,” Jones mused.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Congress in 2021 proposed the “Saving American History Act” because of Hannah-Jones, who said, “I created the project, but I didn’t write most of it, except for three chapters. Many historians co-wrote “The 1619 Project.”

She continued, “There are 1,000 end notes in ‘The 1619 Project.’ We didn’t create new history, we popularized it. It became accessible to regular people.”

What Hannah-Jones said corroborated Temple University scholar Molefi Kete Asante’s statement during the symposium, that what scares the ruling class “is the fear of truth, and mass education as the surest way to mass consciousness.”

During the gathering, Wickham screened a 48-minute video, and interview with his mentor, history professor Mary Frances Berry. She cited the routine banning of Alice Walker’s “The Color Purple,” “The Autobiography of Malcolm X,” co-written with Alex Haley, and “The 1619 Project.” Berry also noted acts throughout American history that marginalize or ridicule Black literature and history:

* Thomas Jefferson denounced and defamed Phyllis Wheatley for writing poetry because it was considered a form of resistance. An 18th-century Black woman was not supposed to be capable of writing;

* During the Civil War, apologists referred to slavery as “school” for Negroes;

*Society marginalized Black inventors – busy during the Industrial Revolution – for defying inequality.

“Book banning now is the action of school boards,” she continued. “Previously it was the actions of states. Moms of Liberty said they don’t want their children to feel uncomfortable. Moms of Liberty asked the government to take the Black books off the shelves.” It was the workaround of a U.S. Supreme Court First Amendment decision affirming free expression.

In response to an audience question, “What can we do?” Berry said writer’s organizations are pushing back, i.e. Kimberle Crenshaw of the African American Policy Forum, Ta-Nehisi Coates, and children’s author Jerry Craft.

Still, libraries hide books. During 2023, reported the American Library Association, 4,200 books were banned in 23 U.S. states; 3,000 of those [72 percent] were banned in Gov. DeSantis’ Florida.

Michael Cottman is author of “The Wreck of the Henrietta Marie,” [1998] his account of a sunken 1698 slave ship near Key West, Florida. Cottman learned to scuba dive, inspired by watching 1960s TV drama “Sea Hunt” as a child.

Cottman said that he received correspondence that the book was pulled from libraries, or returned books arrived stamped “discard,” or “no longer property of,” or, specifically, “no longer of interest to the Denver [or Fayetteville, North Carolina, or Cheyenne, Wyoming” libraries.

Overall, various libraries in 11 U.S. states and Winnipeg, Canada., pulled his books.

“One thing that scared readers,” said Cottman “was the National Association of Black Scuba Divers [depicted in his book]. We’re not associated with water unless in slave ships.”

Cottman referenced a conversation he had years ago with an Oxford University professor who asked, why didn’t he focus on the artifacts of the enslaved Africans buried on the ocean floor. The author answered, “Black people didn’t bring luggage.”

You must be logged in to post a comment Login