“In addition to being one of our greatest players, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar has devoted much of his life to advocating for equality and social justice. With this new award, we are proud to recognize and celebrate NBA players who are using their influence to make an impact on their communities and our broader society.”

— NBA Commissioner Adam Silver

By Marc Morial

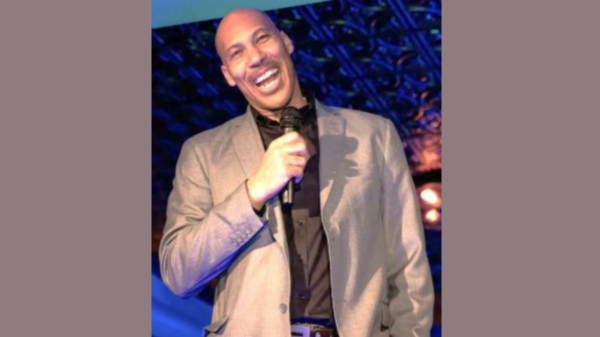

Credit: Courtesy: Jabbar’s website

Three decades after retiring from the NBA, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar remains the League’s all time leading scorer and still holds the record for the most MVP awards, the most field goals, most All-Star selections, and the most minutes played.

In the years since, he has found success in a variety of pursuits: coach, cultural ambassador, even reality television contestant. But his greatest achievements off the court have been as a writer and civil rights activist.

Now, the NBA has honored him by creating a new award to recognize the player who best embodies his pursuit of social justice and racial equality.

The first Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Social Justice Champion award will be announced during the playoffs. The winner will receive $100,000 to donate to an organization of his choosing. Four additional finalists will receive $25,000.

It is my honor to serve on the committee that will select the winner. Throughout his impressive career, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar has been an uncompromising example of leadership, excellence and integrity.

Abdul-Jabbar – then known as Lew Alcindor – emerged as a basketball phenomenon as a student at Power Memorial Academy in New York City in the early 1960s as the Civil Rights Movement was reaching a crescendo. The 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in 1963, when he was 16, awoke a deep anger within him.

“As I watched the ineffectual moral outrage of the black southern preachers, the cold coverage of the white media, and the posturings of the John F. Kennedy White House, my whole view of the world fell into place,” he wrote in his 1983 autobiography, Giant Steps. “My faith was exploded like church rubble, my anger was shrapnel.”

A few months later during a game, he was devastated to hear his trusted coach use the n-word when berating his playing. Determined not to return to the coach’s basketball camp in the summer of 1964, he accepted a summer job as a reporter in the Harlem Youth Action Project’s journalism workshop.

Though he later relented and attended the camp in August, he began his summer working out of the 135th Street YMCA Annex and devouring the collections of the Schomburg Center for Research In Black Culture on Lenox Avenue. On July 18, Harlem erupted in rioting in response to the shooting death of a Black teenager by an off-duty police officer.

“We interviewed people all over the Harlem streets and got exactly the angry, ghet-to-dialect, eyewitness reports that white journalists and newscasters have such a hard time accepting at face value,” he wrote. “Newspapers and TV broadcasts focused on property damage and police injuries, not Harlem’s powerlessness.”

As a student at UCLA, he was among a group of prominent Black athletes inspired by Muhammad Ali who supported a boycott of the 1968 Olympic games to protest racial discrimination. Though no formal boycott was announced, he declined to participate and spent the summer teaching basketball and mentoring children as part of New York City’s Operation Sports Rescue.

“I thought then and think now that the pride I instilled in those hundreds of inner city black kids by teaching and paying attention to them was ultimately worth more than whatever I could have contributed to the national morale in the way of an Olympic gold medal,” he wrote.

In addition to several autobiographies and mystery novels, Abdul-Jabbar has published books about the Harlem Renaissance, Black inventors, and forgotten Black heroes like the 761st Tank Battalion, belatedly awarded the Presidential Unit Citation in 1978 for extraordinary heroism in World War II, and Bass Reeves, first Black deputy U.S. marshal west of the Mississippi River.

As racial justice protest swept the nation last year, he wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Racism in America is like dust in the air. It seems invisible – even if you’re choking on it –until you let the sun in. Then you see it’s everywhere. As long as we keep shining that light, we have a chance of cleaning it wherever it lands.”

Marc Morial is president/CEO of the National Urban League.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login