By Jamie Landers and Kelli Smith

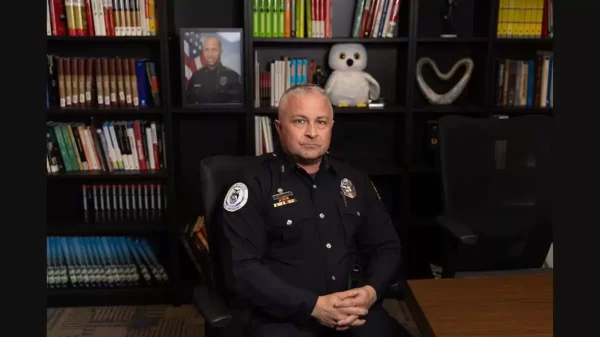

As communities across southern Dallas grapple with the aftermath of two mass shootings in only two weeks, police Chief Eddie García remains adamant that his officers care about the region and are actively planning to better protect its people.

Residents say a lifetime of experience has them bracing for broken promises — and more gunfire. The shootings left two dead and 25 wounded.

“It’s an old conversation,” said Travis-Lee Moore, president of the nonprofit Heritage Oak Cliff, “and it’s sad that it takes incidents like last weekend for it to trend.”

García said in an interview with The Dallas Morning News that the department invested resources in the southern part of the city before the shootings — one at a concert and another at a party. He said many of the small grids where the department heightened its presence in recent months were in southern Dallas, which has helped violent crime drop there overall.

“Although the data doesn’t support that we don’t care, if people feel that way, then we need to look at ourselves and figure out why it is they feel that way and try to fix the perceptions,” García said.

“If we did not care about southern Dallas, we wouldn’t have a plan,” he added.

Yet people in the communities that make up the southern part of the city expressed frustration when they spoke with The News, saying there is a disconnect between them and the police. They say the problem isn’t something the Police Department alone can solve. It will take an investment by the city in better education, mental health resources and opportunities for children.

Department statistics updated Thursday show that even with the recent shootings, violent crime is down in the region’s three police divisions. Across the city’s southeast, south central and southwest divisions, there have been 1,493 violent crimes this year — 215 fewer than this point in 2021. Neighborhoods in those divisions include north, west, east and southeast Oak Cliff, Red Bird, Mountain Creek, South Dallas, southeast Dallas, Pleasant Grove and Rylie.

The murder count across southern Dallas is about the same as last year, according to the department’s official tally. There have been 38 murders in southern Dallas this year, one fewer than during the same period in 2021. Police tallied 1,129 aggravated assaults, 118 fewer than last year, and 277 robberies, a decrease of 29 compared with 2021.

Even so, a spate of shootings over the past month has left southern Dallas with more questions than answers, most recently in the face of what happened April 2at an unpermitted outdoor concert in the 5000 block of Cleveland Road. The shooting killed Kealon Gilmore, 26, and wounded 16 others ranging in age from 13 to 29.

No arrests have been made, and officials have not provided information about potential suspects. Seven off-duty Dallas police officers were working security at the event but left about 30 minutes before the gunfire, when police said their shifts ended.

“It just infuriates me that we were doing this concert without any sort of permit and the cops were working,” Moore said. “How in the world did we miss all those checks and balances?”

How police supervisors approved the officers to work off-duty at an event without a permit troubles García, too. After the shooting, he changed department policies to ensure that such approvals aren’t made for events without permits.

That gunfire followed a shooting two weeks before in which one teen was killed and nine others were wounded at a spring break party at The Space Dallas, a South Dallasparty venue. The chief has said that event also didn’t have a permit.

The Space Dallas and St. John Missionary Baptist Church — a church on Marsalis Avenue in east Oak Cliff that owns the property where the concert shooting happened — have not responded to requests for comment.

New police policies

García implemented new policies thatstate off-duty officers areno longer allowed to work events that require a permit and arenot issued one. He said Friday that police plan to be more vigilant going forward, and will improve their internal communications.

“We’re not perfect,” he said. “There’s not a police department in America that’s perfect — I wish we were. To the extent that we can increase communication we have amongst each other is what we’re going to do, to do our best to avoid this from happening.”

García said 23 of the 47 grids in Dallas where police focused efforts the past 90 days as part of the chief’s violent-crime plan are in southern Dallas. He said officers have been out across the area not only weeding out crime, but also infusing positivity so people don’t only see police “in a moment of crisis.”

But it’s never enough, according to García.

“We can’t do this alone,” he said Friday in an interview. “We need our community to be our eyes and ears.”

‘Root of the problem’

Akwete Tyehimba, the 59-year-old owner of the Pan-African Connection Bookstore and Resource Center in east Oak Cliff, said she has noticed not only an increased police presence in the past six months, but “a notable, intentional effort” to better community relations.

Tyehimba said thatas recently as Wednesday, two Dallas police officers came to the plaza in the 4400 block of Marsalis Avenue and spent nearly two hours talking to community members both inside and outside the businesses. She also noted the department has consistently sent Black or Hispanic officers.

“You feel at ease with people who look like you,” she said, “so I think they really are trying.”

Those efforts, however, are misdirected, she said.

“It’s not about a lack of officers — it’s a lack of mental health resources, a lack of education, a lack of support for the youth in this community,” Tyehimba said. “These streets are telling them who they are before they have a chance to decide for themselves. Police can’t change that. Only community can change that.”

García said the department doesn’t requireofficers to work at particular stations. Officers instead bid on where they hope to be placed. He said there’s diversity at every station, and the department is always working toward better reflecting the city.

A New York Times report published in September 2020 said the Dallas Police Department is 21% more white than the Dallas community but had “narrowed the gap between the share of white officers and white residents when comparing 2016 with 2007.”

“Listen, do we need to get better at diversity? Of course we do,” the chief said. “Every department does and we’ll continue to strive for that. No question about it.”

Robert Bean, 73, has lived in southern Dallas his entire life and said he feels the area has been “left behind” by the department.

“They keep saying things will be different; that we will do this, this, and that and it never happens,” Bean said. “People here don’t choose to be violent out of nowhere. There is real pain running deep in this part of the city and it’s made worse by broken promises.”

Bean said the issues that need the most attention in southern Dallas include drug use, gang violence and a lack of opportunities for residents like him with criminal records, especially in terms of housing and employment.

“Police on patrol just passing through? That makes no difference for people like me,” he said. “The root of the problem doesn’t leave with them.”

‘A day in the life’

Moore, the president of Heritage Oak Cliff — a nonprofit that represents about 30 neighborhoods across Oak Cliff — said residents weren’t surprised by the concert shooting last weekend or other instances of violence across the area.

“It’s just kind of a day in the life — and, of course, it’s heartbreaking,” he said.

Moore said the southernpart of Oak Cliff has little police presence, and City Council members and city leaders tend to pay lip service to problems instead of coming together and investing in the community.

“I love that Chief García is saying these things, but I’m not seeing any results,” he said. “The residents are frustrated. And I know the cops are frustrated. Everybody’s frustrated, and I don’t know how to get everyone not frustrated and back to the table to talk about how to make things better down here.”

James Hauck, vice president for communications of Heritage Oak Cliff, said it’s common to hear gunfire and engines roaring every night with speeding cars and drag racing in his neighborhood in a southern part of Oak Cliff, near Kiest Park.

“I have sat here sometimes and said, ‘When is the bullet coming through the ceiling, right?’” Hauck said. “Because it happens. I don’t have a neighbor who hasn’t replaced their roof who doesn’t have bullet holes in it.”

Moore and Hauck said north Oak Cliff seems to receive more attention than farther south. Hauck said the southern part of Oak Cliff can seem like “the wild, wild west” because people do whatever they want without getting caught.

“It’s sad because it’s happening so often …it’s no longer a shock,” Hauck said. “Now we’ve just sort of taken this in and we ingest this as a normal part of life. It’s just becoming more frequent.

“The closer it gets, the scarier it gets.”

You must be logged in to post a comment Login